Christopher Havens, a gifted mathematician, spiraled into addiction and murdered a man in 2010, earning 25 years in prison. In solitary, math worksheets sparked obsession; self-taught, he solved advanced problems and co-authored papers on continued fractions. But his greatest equation? Redemption

Growing Up and the Road to Washington State Penitentiary

From as early as he could remember, Christopher Havens had an exceptional mind for mathematics. His mother, Terry Forte, a nurse and Army veteran, remembers how quickly her son grasped complex ideas. “I was never particularly good at math,” she once said, “so I couldn’t believe how easily it came to him.” By fourth grade, he was so far ahead of his peers that teachers often asked him help teach those who were struggling.

But while numbers came naturally, fitting in did not. Forte’s military service meant a lot of moving, meaning Havens was always the “new kid.” Havens describes his younger self as “never popular and a little awkward,” but desperately wanting to fit in. The combination of trying to fit in, then moving on before he could, became the theme of his early years and left him with a feeling of unease – a tension – that he found impossible to soothe.

In his teenage years, Havens began experimenting with marijuana and alcohol—then gradually with hallucinogens, painkillers, and methamphetamine. “He wasn’t a bad kid,” Forte would later say. “He’d give the shirt off his back for anybody.” But by the time he reached high school, he was unrecognizable from who he had been just a few years earlier. He was using heavily, skipping classes and, in his sophomore year, he dropped out completely.

Years of addiction blurred his memory of those years. “There are big patches that are just fuzzy,” he would later admit. He drifted through his twenties, occasionally finding work—most recently at a Denny’s in Olympia, Washington—before losing his job to meth use. By 2010, Havens had slipped deeper into the drug trade, selling meth to support his habit.

That same year, his life unraveled completely. Amid paranoia and addiction, he became entangled in a violent confrontation with two men he had been selling drugs with. Havens would later describe the events as “foggy,” but the outcome was devastating: one man dead, and Havens charged with murder.

His mother still remembers the phone call. “When the police first called and said he was in jail for murder, I told them, ‘No, he’s not,’ and I hung up,” Forte said. “Then I called back.”

In 2011, Christopher Havens was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 25 years in Washington State Penitentiary. He was 30 years old—a gifted mathematician whose life had veered tragically off course.

Yet, behind the prison walls where his story might have ended, a remarkable transformation was only beginning.

An Awakening: Rediscovering Mathematics

When Christopher Havens first entered Washington State Penitentiary, he thought survival meant fitting in. “During a phone call from prison, my father asked if I was going to be a clownfish in a sea of sharks,” Havens later recalled. “I chose shark.” That decision—joining a prison gang—quickly landed him in trouble. Solitary.

The isolation was excruciating. The cell was tiny, always bright, and the noise was unbearable. All day the other prisoners would shout, clang metal cups on metal bars, and generally make as much noise as they could. Sleep was impossible. To pass the time, Havens began working on Sudoku puzzles — a brief respite from the chaos. But soon, even those weren’t enough. “I realized the same need to belong that got me into trouble had brought me here,” he said. “I needed to find a different kind of purpose.”

That purpose arrived in the form of a prison employee known to inmates as Mr. G. Each day, Mr. G. slid packets of papers under cell doors. When Havens finally asked for one, he discovered it was a bundle of algebra worksheets. He began solving them obsessively. “It got to where it was all I was doing,” he said. “I was staying up all night.”

For weeks, Mr. G. corrected his work and handed him new packets. Eventually, Havens asked for harder material—trigonometry, then calculus. One day, instead of worksheets, Mr. G. slipped a note through the slot. It read: ‘Mr. Havens, you have surpassed my abilities. Good luck.’

For the first time in years, Havens felt a sense of peace and direction. “I’d been a decent petty thief and a great drug addict,” he said. “But solving problems gave me something good to be good at.” He threw himself into mathematics, teaching himself advanced topics and filling notebooks with long sequences of numbers and symbols. When he called his mother, Terry Forte, to ask for trigonometry and calculus textbooks, she was surprised—but not shocked. “If he sets his mind to something,” she said, “he doesn’t stop until he’s mastered it.”

By the time Havens was released from solitary, he had little interest in prison politics. “At that point, I was more concerned with my education than anything else,” he said. “Eventually, one of the guys told me, ‘You don’t belong with us.’ And I realized he was right.”

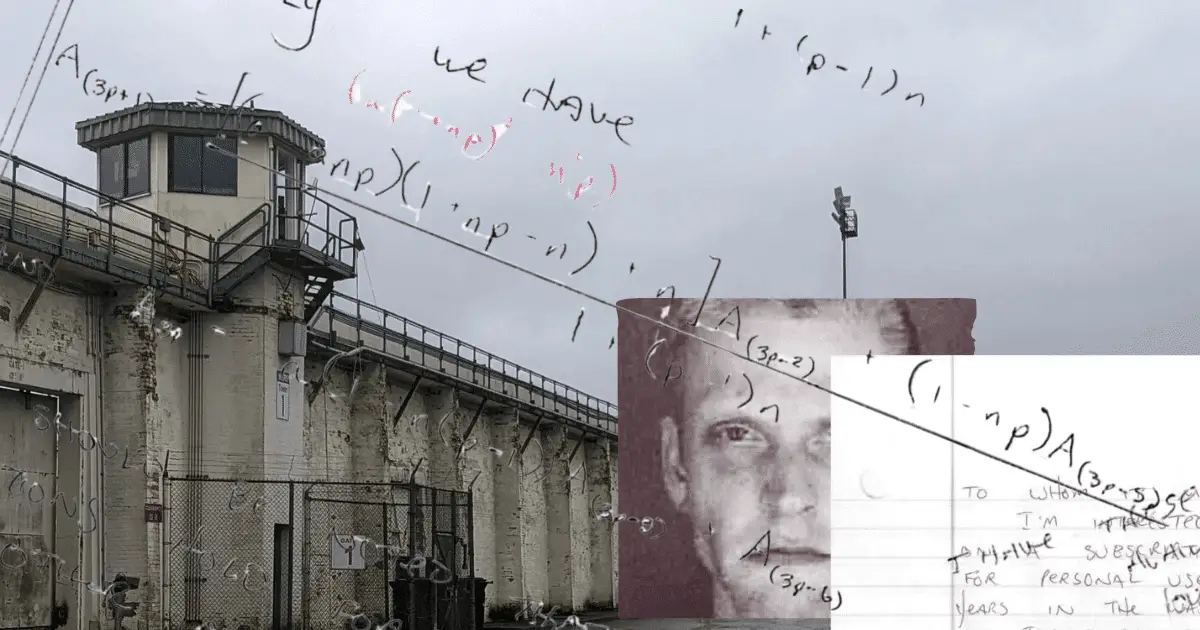

Still, teaching himself higher mathematics from inside a cell had limits. Without internet access or instructors, he often hit dead ends. So in 2013, Havens wrote to the Mathematical Sciences Publishers, explaining that he was serving a 25-year sentence and seeking guidance. “Numbers have become my mission,” he wrote. “Is there anyone I could correspond with?”

That letter eventually reached Dr. Umberto Cerruti, a number theorist at the University of Turin in Italy. At first, Cerruti assumed it was another message from a well-meaning amateur. To see whether Havens was the real deal or not, he sent him a problem that would challenge most university students.

Several weeks later, a parcel arrived from Washington State Penitentiary. What was inside was extraordinary – a roll of paper more than a meter long, completely filled with handwritten equations. When Cerruti entered the formula into his computer, the results were perfect. And what he had initially dismissed as another crackpot prisoner turned out to be genuine mathematical insight.

Intrigued, Cerruti invited Havens to work with him on a project exploring continued fractions—a field about how numbers can be expressed as layered, repeating sequences. Across thousands of miles, through handwritten letters and calculations, the two began to exchange ideas.

In January 2020, their research was published in Research in Number Theory, a peer-reviewed mathematics journal – a remarkable acheivement for any mathematician, let alone one working in a prison cell—without a computer, internet access, or even the ability to see his own equations rendered on screen.

That collaboration marked a turning point. Mathematics had given Havens not only a new identity but also a sense of connection to a world far beyond prison walls. “Working with others on the stuff of our imagination in such a way that adds—even a tiny bit—to the wealth of human knowledge was priceless,” he said. “It was the most beautiful thing I had ever experienced.”

Havens later went on to collaborate with Dr. Carsten Elsner, a mathematician in Hanover, Germany, with whom he co-authored several more papers. Though he had no access to a computer, Havens learned to write his work in LaTeX, the coding language used for mathematical typesetting, visualizing every symbol and equation before mailing pages of source code to his collaborators. “He’s analytical and I’m creative,” Havens said. “Our minds just click.”

From the harsh silence of solitary confinement, Christopher Havens had found a bridge to the wider world—built not of steel or stone, but of logic, discipline, and the infinite beauty of numbers. Through continued fractions, he had, in a sense, reassembled the pieces of his own fractured life.

Turning Redemption Into Reform: The Prison Math Project

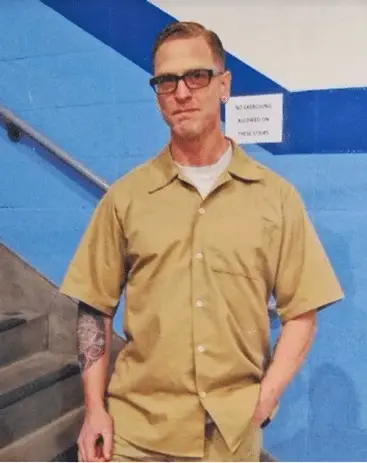

Christopher Havens still has more than a decade left on his 25-year sentence—14 years, or 12 with good behavior. By the time he walks free, his five children will be grown, some possibly parents themselves. Yet Havens doesn’t see these years as lost time. Instead, he views them as a rare opportunity to rebuild his life from the inside out. “Most inmates wait until release to start their career,” he says. “Not me. I am going to redefine what productivity looks like in prison.”

That redefinition began in 2016, when Havens launched the Prison Mathematics Project (PMP)—a nonprofit initiative designed to help other incarcerated individuals discover purpose and structure through the study of mathematics. Inspired by the same system that had transformed his own life—Mr. G.’s humble math worksheets—Havens’ program begins by sending study packets to inmates across the United States. From there, each participant is paired with an academic mentor who provides personalized guidance and introduces them to the wider mathematical community.

“My mission,” Havens says, “is to change lives by reversing recidivism through mathematics.” He believes the discipline’s order and logic can rewire the mind, cultivating patience, discipline, and self-worth. “Mathematics and its culture have an incredible impact on the human heart,” he wrote in a program statement. “Rehabilitation and justice happen in the most meaningful ways when people see that something beautiful and purposeful can exist within them.”

The early success of PMP was interrupted by administrative red tape. When a corrections officer declined to oversee the program, it was quietly shut down. Then, the COVID-19 pandemic halted all prison education nationwide. But Havens refused to let the idea die. Around that time, as media attention grew following the publication of his research on continued fractions, a message arrived from a 15-year-old high school student named Walker Blackwell. The teenager wanted to help Havens take the Prison Mathematics Project national. At first, Havens was skeptical—“I thought, he’s too young,” he recalled—but Blackwell’s enthusiasm mirrored his own. With the support of Blackwell’s parents and another collaborator, Jack Smith, they relaunched PMP as a nonprofit organization.

Together, the small team rebuilt the project around a simple principle: to replicate the environment that had allowed Havens to transform his own life. Today, the PMP connects incarcerated learners in the U.S. and Canada with mathematicians, researchers, and educators who volunteer as mentors. It provides not only study materials but also a sense of belonging—something Havens calls “the biggest factor in breaking the cycle of crime.”

The organization has since developed an innovative digital tool, the PMP Console, which allows prisoners to learn programming languages like Python, R, and JavaScript through a prison email system. Because most inmates are prohibited from using computers, the PMP Console simulates a coding environment—participants write code, send it to PMP, and receive compiled results as messages in return. “It’s not fast,” Havens admits, “but it’s a game changer.” He learned Python using this same system.

While building the PMP, Havens has continued to deepen his own studies. His fascination with cryptography—the use of mathematics to protect information—grew naturally from his work in number theory. “Cryptography is equal parts logic and mathematics,” he says. “It’s also about solving problems that seem impossible.”

That idea resonated with Dr. Amit Sahai, a leading cryptographer and professor at UCLA, who began corresponding with Havens after reading about his work. Sahai describes him as “easily among the most diligent students I have ever had the pleasure of working with throughout my entire academic career.” He adds:

“Over the past few weeks, he has solved advanced problems that few of my UCLA undergraduates could solve in teams—even though Christopher is working alone, in what we can euphemistically call an ‘adverse environment.’”

For Havens, cryptography represents both a professional and symbolic pursuit. In its essence—the preservation of truth and the concealment of meaning through mathematical order—he sees a reflection of his own story: chaos transformed into structure, isolation transformed into connection. “What I love about cryptography,” Sahai once said, “is that we try to achieve impossible goals. Sometimes what seems impossible turns out to be possible.” He could just as easily have been describing Havens himself.

Today, the Prison Mathematics Project continues to grow despite limited funding and institutional barriers. It has helped multiple incarcerated researchers publish their own work in professional journals and inspired discussions about juvenile versions of the program for young offenders. “Imagine what prisons would look like,” Havens muses, “if there were more anomalies—people doing amazing things—than the garden-variety convict.”

For Christopher Havens, mathematics has become more than an academic pursuit—it is a philosophy of redemption, a blueprint for human transformation. Through equations, mentorship, and perseverance, he is proving that even within the rigid confines of prison, something infinitely expansive can still unfold: the ability to rebuild not only one’s mind, but one’s humanity.

Want to hear from the man himself? This Numberphile podcast features Christopher Havens, a prisoner who finds redemption through advanced mathematics. The interview details Havens’ journey from a life of crime to publishing academic papers and creating the Prison Mathematics Project. Listen to discover how a passion for numbers transformed a life.